July 16, 2024

Many small pull requests

Okay, so you are working on a new feature. Because your team operates using a pull request-based workflow, someone needs to review your code before it lands in the main branch and is released to all users. In the last retrospective, there was a lot of frustration among peers because code reviews usually take hours or even days to complete, and still, there is a lot of rubber-stamping or minor comments about code style (things that could be easily automated with better linters).

This time, you will try to approach it a bit differently and optimize for reviewing rather than your own immediate productivity (which gets hurt in the long term anyway due to delays in code review). Based on your experience as a reviewer, code reviews start to get complicated not when they involve many file changes but when they change multiple behaviors at the same time. For example, a pull request with 300 file changes where you're simply renaming a constant is much easier to review than a pull request with 4 file changes that modify four different system behaviors.

This time, you plan to slice your work in a way that you can create more than one single pull request, ensuring each pull request only introduces one new behavior into the system (a variable rename, a change to existing logic). The only problem with this approach is that no one on the team operates this way, and you are unsure whether it is possible to merge incomplete feature code into the main branch or if there is a way to hold off on all the changes but still allow for incremental reviews.

A few months ago, someone from the billing team shared a recent experiment using feature flags to turn on and off certain logic in production based on a configuration that’s easily accessed by a UI. Leveraging feature flags sounds like a sensible approach. That way, you could wrap all the new code under a feature flag that’s deactivated by default and only enabled once all pull requests have been merged into the main branch and the feature is code complete. But it seems the feature flag infrastructure is a bit experimental in the company, and you’re unsure whether it will be safe for your team to start relying on them.

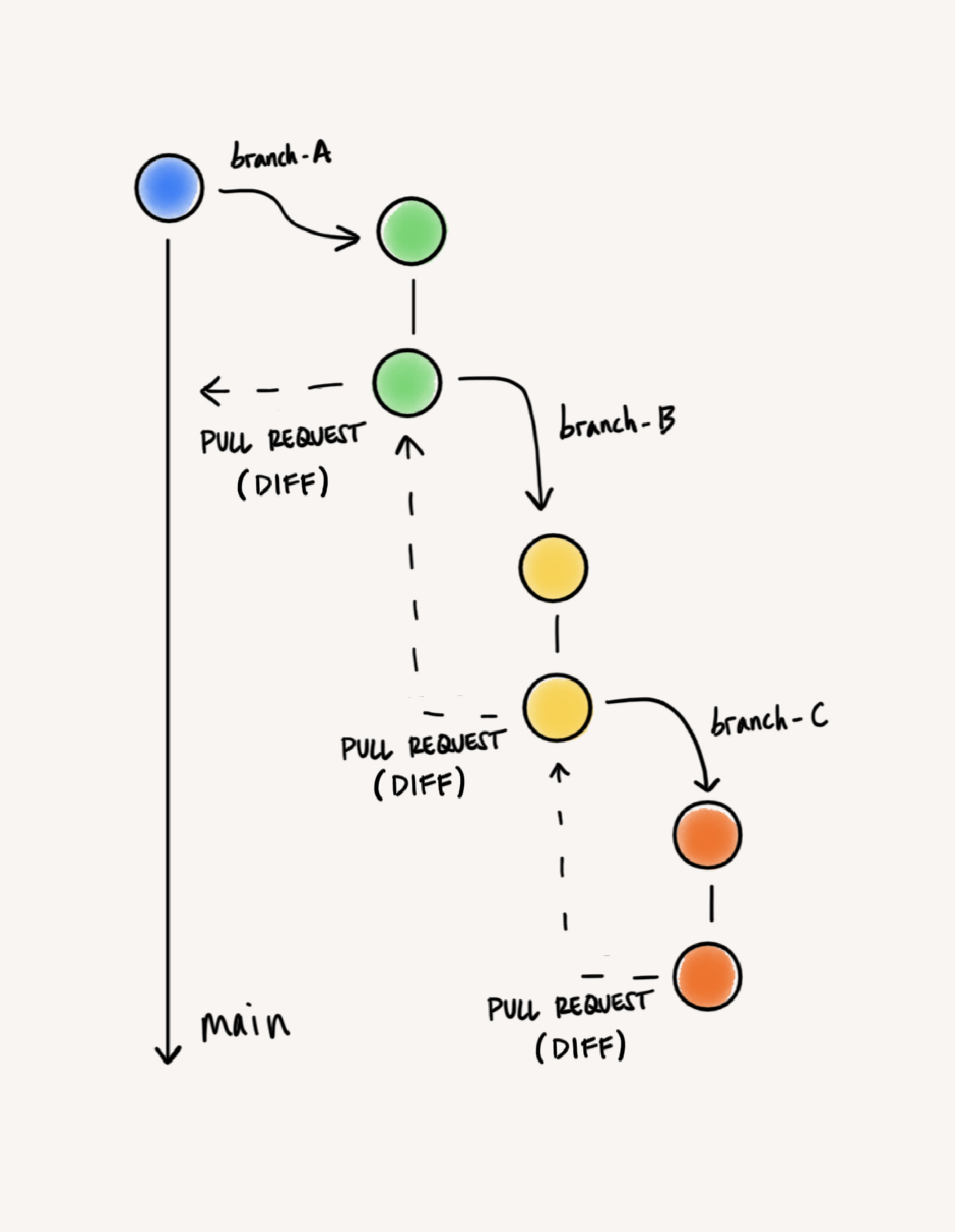

But wait, there might be ways to achieve a similar code reviewing experience (note from the author: yeah, deploying code behind feature flags offers many more benefits than just facilitating code review, but that’s part of another series) by stacking pull requests. For example, you can create a first branch for your initial set of changes and then branch off again with the new set of changes. This second pull request will be based on the first branch instead of the main branch, so the diff is clear and only shows the new set of incremental changes.

Although stacking pull requests may become a bit tricky with large feature developments, it offers a good compromise for small to medium developments. You just need to make sure each new set of changes branches off from the previous branch. Then, each pull request will use the previous branch as the base branch for comparison. You don't need to merge each pull request independently; they are there just to facilitate the code review process. Once each step has been approved by your team, you can create a final pull request containing all the changes and use that to release the code. It's true the process accounts for some minimal duplication, but the benefits of having small, reviewable units persuade you to give it a try.

The only problem: you have never worked this way before, and typically, your feature development is a bit chaotic. Although you know the end goal, you’re usually figuring out the way to get there as you experiment with the codebase. This time, however, you may need a clearer plan to slice your work correctly for reviewing, following the principles you stated before (each pull request will only contain one change in behavior).

All your teammates have small differences in the way they approach feature development. Thinking about it for a second, you realize Sara uses something she calls an “Implementation Plan” and regularly posts it as a comment on the issue even before writing a single line of code. Reflecting a bit more, each step in Sara’s implementation plan typically matches the principles you’ve stated before: each pull request introduces only one new behavior into the system.

Deciding to follow Sara’s approach, you take a few hours to design a possible solution for the problem. There might be a few surprises along the way, but the implementation plan looks solid and has already given you some hints about how you may slice the problem. You have already identified a little refactoring you need to accomplish in the first instance that is better encapsulated in its own pull request so Jose, one of the experts on that part of the system, can take a look. Actually, now that you look at the plan, you realize it might be a good moment to ask Sofia, the tech lead for your team, to chime in so she can give you a thumbs-up now that you haven’t invested too much time in development. Working in smaller batches has already proven to be helpful even before creating the first pull request.

--

So, the little story above is just an example of how we may approach software development in a way that favors creating many small pull requests instead of a single one. Obviously, your mileage may vary, as may the experience around your team, but regularly incorporating this notion of 1 pull request = 1 behavior should facilitate both your development (because you’ll be working with less complexity at every step) and your code review process.

Implementation plans are just a technique that may help you divide your work in a way that makes sense and follows the principle we’ve stated before. They may also contribute to other benefits such as discovering potential blockers, incorporating feedback from your colleagues early in the process, or offering you some guidance as you move forward with the development.

We have already covered how stacking pull requests may work at a high level. Some tools support this kind of process by default (e.g., Phabricator via stacked diffs), but a similar workflow can be easily replicated in tools such as GitHub or GitLab (although the developer experience could be much better).

But as with almost everything in software, there isn’t a silver bullet. One drawback of slicing your work this way is that reviewers may find it more complex to see the whole picture of your changes. While this can be minimized by offering links to previous pull requests, having all your changes in a single pull request can make it easier for them to understand the context and scope. On the other hand, a large pull request with dozens of changes can also be overwhelming and, as we have discussed before, delay the overall reviewing process because reviewers need to deal with more complexity.

If you're looking for cost-effective ways to improve the code review process on your team, give stacked pull requests a try or, at the very least, aim to conform to the rule of one behavior change = one pull request.